For my next quest, I mean to read through the eight volumes of Henry Adams The History of the United States of America, which looks exclusively at the administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. I plan on one post for each. Each volume of this massive history covers two years, roughly corresponding with one session of Congress.

Adams is interested in this period for a variety of reasons, all of which should still be of interest to us today looking back at history for lessons on unintended consequences of our actions, or more bluntly on how to sustain our values in the face of historical change. One of his interests in is how Jefferson’s “revolution of 1800” was undone by himself and his successor, James Madison. In almost every area, Jefferson’s vision of government was challenged by the international systems and the changing nature of the American economy. He is also interested in the growth of an empire (commercial, territorial) in the aftermath of America’s anti-imperial revolution. Thirdly, he is exploring the maturation of democratic values and the final triumph over aristocracy. One thing that makes this account so very relevant today is that he was one of the first who detailed a clear narrative of America’s place in the world in its early history. Much of Adams’ curiosity is with the Atlantic and the diplomatic relations with Europe. At a time when historians were obsessed with the frontier, Adams looked abroad seeing the United States within a world system. With these themes in mind, we can being to approach the lengthy text.

Adams starts with a very useful survey of the geographical, economic, and intellectual conditions in the United States in 1800. Adams lived at a time when the United States’ conquest of the continent was more or less achieved. Less than one hundred years earlier, the United States was fragile, with a small population, and great internal divisions. While he may have seen the eventual rise of the United States as inevitable, he makes it clear that no one would have thought it likely at the time of Jefferson’s presidency. The two main divisions running across the United States were political and sectional. The political division (working at both the local and the national level) is not just between the Federalists against the Jeffersonian republicans. There was a deeper division between the conservatives who held onto the some of the major assumptions about leadership carried in from aristocratic societies. Facing this was a growing democratic society, helped along by the relative equality of conditions compared to Europe. He also details a deep sectional divide in the realm of the mind. Now, I suspect there is some teleology in this given that Adams is writing after the Civil War, but his case is fairly convincing. What seems to be going on is not that one section lacked what could be called a ruling class, they all had that (true aristocrats in the South, a more religious and traditional communitarian elite in the North). In the Middle Colonies, a more apparently democratic society was able to flourish. “New York possessed no church to overthrow, or traditional doctrines to root out, or centuries of history to disavow. Literature of its own it had little; of intellectual unity, no trace.” (77) But generally, across the nation what matter was how this division was interpreted based on the local conditions.

In a brilliant little chapter called “American Ideals, 1800” Adams lays out the fundamental divisions between the United States and Europe. Conservatives, in a sense, looked back to Europe. “[They] could tolerate no society without such pillars of order. . . The Church was a divine institution. How could a ship hope to reach port when the crew threw overboard sails, spars, and compass, unshipped their rudder.” (122–123). But despite their shouts, the American social system was doing just that. Yet democracy was untested when Thomas Jefferson was elected president. He was one of its spokespeople, but there was yet an American language, an American literature, an American science. Its innovations, such as they were, were social and visible in existing reality, but whether that could create something new or would become disastrous was the test that Jefferson’s party faced.

Whatever radical visions Jefferson had for the United States, as detailed in his 1801 message to Congress were focused on reducing the role of the executive. These were almost immediately undermined by foreign policy challenges: first a war against the Barbary Pirates and second developments in the Haitian Revolution, which saw an increased interest of France in the Caribbean. Domestically, efforts did go forward to correct the mess left by John Adams last minute appointments to the judiciary and the promises to reduce internal taxations. (I find the fact that the United States survived so long by taxing commerce and not labor interesting.)

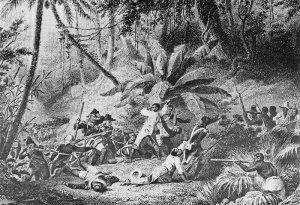

Adams is never only interested in what is going on in the United States. He always saw the young republic in the context of a world system that they did not control, but were note entirely subject to. As much as the continent may be have been a blank slate (it was not, but some saw it that way), the world system was not and the United States could not avoid the challenge of being a part of this competitive and often vile world. Adams spends two chapters talking about the Spanish court and the French interests in the Americas and another on the rise of Toussaint Louverture. The result is we find these United States diplomats a bit out of their league or at least, being pushed into directions they would not like to do. “When Jefferson became President of the United States and the Senate confirmed the treaty of Morfontaine, had Louverture not lost his balance he would have seen that Bonaparte and Talleyrand had out-manoevered him, and that even if Jefferson were not as French in policy as his predecessor had been hostile to France, yet henceforth the United States must disregard sympathies, treat St. Domingo as a French colony, and leave the negro chief to his fate.” (262) This is just one example of this larger scale that Adams always sees these Jeffersonian revolutionaries on.

The first volume of his history ends with more foreign policy problems, due to the French closure of the Mississippi and the closure of the Congress in 1803.