What happened to the motley crew that pioneered a French Protestant community in Florida? In the short-term, it was destroyed but in the long-term it was replaced with a very different formula of empire.

“New England Protestantism appealed to Liberty, then closed the door against her; for all Protestantism is an appeal from priestly authority to the right of private judgement, and the New England Puritan, after claiming this right for himself, denied it to all who differed with him. . . With New France it was otherwise. She was consistent to the last. Root, stem, and branch, she was the nursling of authority. Deadly absolutism blighted her early and her later growth. Friars and Jesuits, a Ventadour and a Richelieu, shaped her destines. All that conflicted against advancing liberty–the centralized power of the crown and the tiaras, the ultramontane in religion, the despotic in policy–found their fullest expression and most fatal exercise.” (312) It is which this diagnosis that Francis Parkman ends the first volume of his massive work on the fate of European empires in North America.

I have not yet seen Parkman deal with the question of slavery, but if slavery (and the general disciplining of labor for a plantation economy) is the original sin of English North America, I wonder if Parkman would agree the victory of the forces of absolutism and the missionary spirit and the seduction of power politics served as the original sin of French North America. Parkman describes in shocking detail the misery and horror of the early explorers and settlers in the Great Lakes. Scurvy, starvation, and conflicts with the Indians ensured that few survived. “A rigorous climate, a savage people. a fatal disease, and a soil barren of gold were the allurements of New France.” (165) It seems to have been a force of will that implanted France’s presence in North America, but it was the will of the state, of absolutist monarchs, and adventures lacking accountability that squeezed from men’s blood and sweat a fledgling colony.

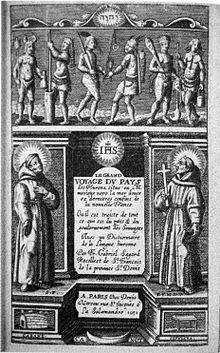

Through good relations in the French court, the Jesuits were able to establish a strong position in early New France, ensuring yet another authoritarian (as Parkman sees it). The Jesuits established the French position in Acadia, despite efforts by the English to displace them. But like everything else in French North America, for Parkman, this was an exercise in autocratic tyranny. “Rude hands strangled the ‘Northern Paraguay’ in its birth. Its beginnings had been feeble, but behind were the forces of a mighty organization, at once devoted and ambitious, enthusiastic and calculating. Seven years later the Mayflower landed her emigrants at Plymouth. What would have been the issues had the zeal of the pious lady of honor preoccupied New England with a Jesuit colony?” (240)

At the same time, as Parkman describes, Champlain is at work setting a foundation in Quebec. Like his masters, Champlain’s goal was not an empire of liberty but the establishment of “the Catholic faith and the power of France.” (241) Parkman blames Champlain, by creating an anti-Iroquois alliance among the Huron and Algonquins, of setting a precedent for diplomatic intervention in Indian affairs. Again, the sin seems to be the imposition of European absolutism and diplomacy on the New World (for a mid-nineteenth century American like Parkman, a horrendous choice). This book The Pioneers of France in North America ends with the decline of Champlain in the midst of Indian wars be entered into unwisely as a product of his patriotic and religious zealotry.

Even the commercial interests of the French in the Great Lakes was corrupted with the taint of absolutism and the absolutist monarch. “The English colonist developed inherited freedom on a virgin soil; the French colonist was pursued across the Atlantic by a paternal despotism better in intention and more withering in effect than that which he lief behind. If, instead of excluding Huguenots, France had given them an asylum in the west, and left them there to work out their own destinies, Canada would never have been a British province, and the United States woudl have shared their vast domain with a vigorous population of self-governing Frenchmen. A trading company was not feudal proprietor of all domains in North America within the claim of France. Fealty and homage on its part, and on the part of the Crown the appointment of supreme judicial officers, counts, and barons, were the only reservations. The King heaped favors on the new corporation.” (314-315)

There are, of course, many more stories to tell, of diplomacy, war, adventure, and the challenge of the English. The main argument of Parkman in his accounting of the era of Champlain is to define the French New World empire as an empire of authority and tyranny, betraying the promise of America.

Our immediate response is to scoff at his prejudices (anti-French, anti-Catholic). As any school-child knows now, the English empire in North America was not less tyrannical. The Puritans were anything but advocates of religious liberty. Virginia became a slave society within a century of Jamestown. Class discipline, capitalism, exploitation, expropriation, and incomprehensible horrors accompanied Europeans of all types in their American adventures. I urge readers to refer to the masterly The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic by Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker for more on these horrors and our ancestors resistance to them. However, whatever his prejudice, Parkman is an ally of liberty and this comes through on every page. And it should give us some encouragement that the “center of civilization”, France, was so horribly ill-equipped politically, religiously, and socially for an new epoch. Champlain was of the middle ages, in Parkman’s view. That liberty even had a chance in America, with all of these forces set against it for so long, might be enough to keep out spirits up.