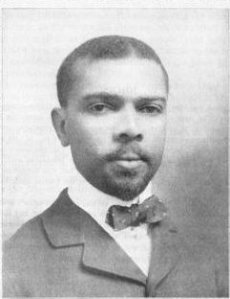

In 1914, James Weldon Johnson became an editor of the newspaper The New York Age, a major African-American activist origin with its roots in the nineteenth century. He would spend the next ten years writing daily editorials for the newspaper. In addition to these editorials, Johnson was an active essay writer and book editor. His work in these areas seems to fall into roughly two areas: articles about African-American cultural or artistic expressions, and articles that can best be defined as propaganda for black activists. Both of his areas of interest remain of interest, but I suspect his work on black culture will have a longer shelf-life.

As you would expect, many of the New York Age editorials take on the political issues of the day, such as Wilson’s expansion of Jim Crow policies into Washington D.C., the production of The Birth of a Nation¸ the Great Migration, the 1919 Race Riots in Chicago, and service in World War I. As far as I can tell, most of his positions on these issues line up pretty closely with W. E. B. Du Bois. The black nationalist argument against serving in the military in World War I was rejected by both because they saw it as a way to reaffirm the importance of black America to the nation. Johnson’s criticism of Marcus Garvey is also similar. In their opinion, Garvey was a megalomaniac who undermined the struggle for social equality by fighting for separation. The Great Migration is an expression of the cultural, social, and economic strength and autonomy of black America, not a deep desire to flee the South or seek separation from America (although perhaps from the white South). There articles are interested to look at and actually provide a good summary into this strain of early twentieth century black thinking.

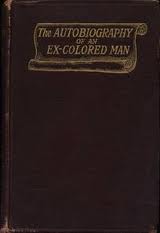

I would like to talk more about Johnson’s cultural logic, because it is where he seems to really shine and where he goes beyond propaganda and politics. His starting point is the fundamental creativity of black people—and it seems all non-whites. It is not just that blacks made a measurable contribution to American cultural life (the narrator in The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man lists four), suitable to be recognized and “celebrated.” Johnson argues instead for an almost Afrocentric position. In an article on “the poor white musician,” he wrote:

The truth is, the pure white race has not originated a single one of the great, fundamental intellectual achievements which have raised man in the scale of civilization. The alphabet, the art of letters, of poetry, of music, of sculpture, of painting, of the drama, of architecture; numbers, the science of mathematics, of astronomy, of philosophy, of logic, of physics, of chemistry; the use of metals and the principles of mechanics were all invented or discovered by darker and, what are, in many cases, considered inferior, races. (619)

Of course, Johnson lived in an era where racial thinking was dominant and it is forgivable that he extends the artificial concept of race to pre-modern achievements (this seems to be the major sin of Afrocentrism).

He makes the same point about contemporary black writers, writing a bold defense and celebration of Claude McKay. (“No Negro poet has sung more beautifully of his own race than McKay and no Negro poet that equaled the power with which he expresses the bitterness that so often rises in the heart of the race.” (647)) If he is defending McKay, he is certainly seeing a deeper purpose of art than mere political propaganda.

Aside from the a collection of the editorials, the Library of America anthology has seven essays and a few chapters from Black Manhattan, Johnson’s exploration of New York after the Great Migration. These were all published between 1919 and 1930. Three of them—“The Riots,” “Self-Determining Haiti,” and Lynching—America’s National Disgrace”—are best looked at as political tracts on some of the major racial issues of the period, specifically colonialism and racial violence. “The Riots” is a succinct argument for the virtue of self-defense against violence, especially when the government fails to protect people through the law. The right of self-defense then falls to the people. “The Negroes saved themselves and saved Washington by their determination not to run, but to fight—fight in defense of their lives and their homes. If the white mob had gone on unchecked—and it as only the determined effort of black men that checked it—Washington would have been another and worse East St. Louis.” (658) This is an important article for the people of Ferguson to re-read today.

“Self-Determining Haiti” is the only essay in this collection that deals directly with US colonialism in the Caribbean, which has been a long-standing question for African Americans since the days of Toussaint. Here, Johnson focuses on the 1914 US occupation. Johnson argues that while there are numerous economic and political causes of the invasion, the root of all US imperialism was racial prejudice. Important for us is the reminder of the collaboration of financial interests and racism. He writes: “And this is the people whose ‘inferiority,’ whose ‘retrogression,’ whose ‘savagery,’ is advanced as a justification for intervention—for the ruthless slaughter of three thousand of its practically defenseless songs, with the deaths of a score of our own boys for the utterly selfish exploitation of the country by American big finance, for the destruction of America’s most precious heritage—her traditional fair play, her sense of justice, her aid to the oppressed.” (687) Notice with me how his language works to fit his own position and his own advocacy within the American tradition.

Johnson’s interest in lynching is about its role in souring race relationship, more than to make an argument for a need for greater legal order. It is takes for granted that lynching is outside of the law, but the solution is not necessarily more law. In fact, there was no shortage of courts in the early twentieth century South. No one was lynched because of a court backlog. If anything lynching was a weapon of white supremacy, which was itself backed by the institutional power of states. Nevertheless, Johnson concludes that the solution to lynching is “good government,” but perhaps that means a bit more than a new anti-lynching bill.

In the next post, I will look at Johnson’s cultural writings and poetry in more depth.