Now it is time to close the book on my companion of the past two weeks, James Baldwin. It was one of the more exhilarating experiences I had since starting this blog because he is so profoundly interested in informal power, the way power functions on the psychological level, building up walls from our childhood. I suppose we would now call this bio-power, but we do not need any philosophical concepts to understand that oppression needs to work on the mental level first. Without a lifetime of institutional, interpersonal, and systemic lessons and disciplining it is unlikely that Jim Crow could have survived as long as it did. Baldwin documents the dismantling of this mental regimen of power. Another theme in his work is what Dubois called “double consciousness” or “the veil.” This refers to the fact that the United States really looked different depending on your position across the color line. As Dubois points out and Baldwin makes clear, black people had the burden (and unique ability I suppose) to look at the United States from the perspective of their own live and experiences as well as clearly understand white America because it was white people who created the superstructure of the color line. White people, privileged to only look at the world through the superstructure they created, are not quite so omniscient. (While I am certain this is generally true, I am not sure it is universal. I do think empathy is possible, but that may be an ahistorical observation.)

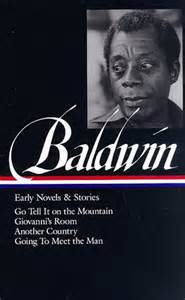

Looking over some of his collected essays included in this volume (there are around 40), arranged chronologically, we can summarize Baldwin’s career into three phases. The first period (1950 until 1961) began with the publication of book reviews and includes his extended period living abroad in France. He is observing the beginnings of the Civil Rights movement but seemed very interested in pursuing a literary life. He published novels that were not novels about race and his essays (which were about race) were attempts to understand the color line.

The second period, from 1961 until the early 1970s, are his revolutionary writings. It is during this time he completes Another Country, The Fire Next Time, and No Name in the Street. His essays from this period are mostly interested in the political issues. His “A Talk to Teachers” is about the ramifications of the revolution for the education of black children. During this period he talked to political figures, engaged in debates, met with Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad, and wrote some of his most provocative essays. “Negroes are Anti-Semitic Because They’re Anti-White” is a good example of this, engaging in a class analysis of black anti-Semitism.

The selections form Baldwin’s final period are slim, amounting to no more than 70 pages. This period is that of revolutionary Thermidor. After the political agitation ended and after the cities stopped burning, Baldwin and other writers turned in part to cultural politics. We have his review of Roots, a defense of “black English” as a language, and at least one essay on sexuality (“Freaks and the American Ideal of Manhood”). What comes out strongly in these essays is that although there were many successes to the revolution, much remanded unchanged. “The Price of the Ticket” is the most somber essay making this point and perhaps a good ending.

When people question my anarchist leanings, the Civil Rights movement often comes up in conversation because one of the historical lessons of Civil Rights is that it took a powerful state to impose itself on the criminal behavior of Southern communities. In this logic, it is at the community level that we are most at risk of losing our freedoms. Only a powerful state can enforce our rights. It is not a bad historical argument, but it does require a whole lot of bracketing of the of the long list of freedoms the state seizes from us anyway, and their defense of capital. Baldwin suggests that atonement cannot be possible be the crimes of racism were perpetuated by a multitude, but it is a multitude that serves the interests of power not one running against it. “A mob is not autonomous: it executes the real will of the people who rule the State. The slaughter in Birmingham, Alabama, for example, was not, merely, the action of a mob. That blood is on the hands of the state of Alabama: which sent those mobs into the streets to execute the will of the State. And, though I know that it has now become inconvenient and impolite to speak of the American Jew in the same breath with which one speaks of the American black, I yet contend that the mobs in the streets of Hitler’s Germany were in those streets not only by the will of the German State, but by the will of the western world, including the architects of human freedom, the British, and the presumed guardian of Christian and human morality, the Pope.” (840)