For my next reading assignment, I have decided to tackle Francis Parkman’s France and England in North America. Combined, this work straddles seven volumes (or 2 Library of America volumes totally almost 3,000 pages). I will approach this text with the single question: What can a left libertarian learn from a mid-19th century Harvard historian writing endlessly about dead empires?

Clues to this can be found on the first page of his general introduction. Parkman writes: “The springs of American civilization, unlike those of the elder world, lie revealed in the clear light of History. In appearance they are feeble; in realty, copious and full of force. Acting at the sources of life, instruments otherwise weak become mighty for good and evil, and men, lost elsewhere in the crowd, stand forth as agents of Destiny. In their toils, their sufferings, their conflicts, momentous questions were at stake, and issues vital to the future world, — the prevalence of races, the triumph of principles, health or disease, a blessing or a curse. On the obscure strife where men died by tens or by scores hung questions of as deep import for posterity as on those mighty contests of national adolescence where carnage is reckoned by thousands.” (13) Parkman is stressing the role of individuals in making history and points out that it is in the frontiers areas, the areas distant from “civilization” that individual makes history. At first glance, this can be a case for not only “history from below” but also for a reorientation of our historical consciousness and our political action to the local level. National history, and unfortunately global history, aggrandizes greatness. Parkman, 150 years ago, was presenting a powerful alternative to the history of great men. How effective he will be at this we will consider as I go through this work.

Parkman also gives what seems to be his main thesis in the general introduction, and it displays a strong anti-French and anti-Catholic prejudice. I am not sure yet if he is saying that English and Protestant values were destined to be victorious. I suspect the work would have been much shorter if that was the case, but he does suggest that the victors were on the right side of history. “By name, local position, and character, one of these communities of freemen stands forth as the most conspicuous representative of this antagonism; — Liberty and Absolutism, New England and New France. The one was the offspring of a triumphant government; the other, of an oppressed and fugitive people: the one, an unflinching champion of the Roman Catholic reaction; the other, a vanguard of the Reform. Each followed its natural laws of growth, and each came to its natural result. Vitalized by the principles of its foundation, the Puritan commonwealth grew apace.” (14) These two perspectives seem at first glance to be contradictory. Either societies and empires develop along natural laws according to their root values (as Toynbee might agree), or individuals in certain circumstances such as frontiers can be the leading force in historical change.

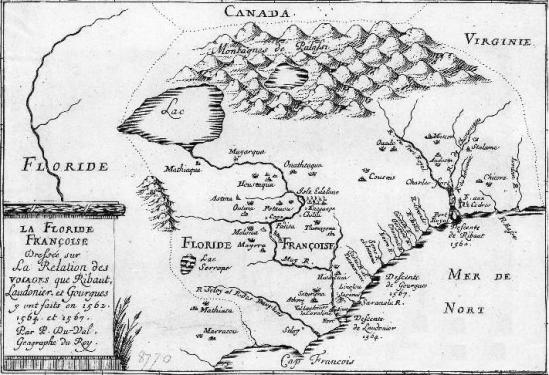

Parkman starts his story in Florida where a struggle between Protestantism and Catholicism began with the French Huguenot attempt to establish a Protestant colony. It starts, with empire at its worst and most paranoid. De Soto’s violent pillage through the lower Mississippi. These expeditions ravaged the Indian communities but failed to lead to a Spanish presence in Florida. While the Pope gave all of North America to Spain, their presence was limited in the 16th century, leading to the paranoia that would result in tragedy for the French Protestants.

The French Protestant expedition reminds us of the English Protestant emigration of a century later. Religious dissenters, displaced peasants, and frustrated working people crammed onto a ship for the new world. “The body of the emigration was Huguenot, mingled with young nobles, restless, idle, and poor, with reckless artisans and piratical sailors from the Norman and Breton seaports.” (37) Just the type of motley crew required for an empire of liberty. Their first attempt was at Rio Janeiro and failed much like the later colony or Roanoke. Attacked by the Portuguese and plagued with internal religious divisions (Catholic, Lutheran, and Calvinist) the leader Villegagnon fled and the settlers dispersed among the Brazilian Indians.

In 1562 a second attempt was made by the sailor Jean Ribaut and he chose the coast of Florida for the colony. Through diligent work and the aid of the local Indians, the colony survived but its role was not clear. Would it be a bastion of the French military in the New World to aid in its conflicts with Spain or would it be a Commonwealth – a model of free people?

The colony, Fort Caroline, was populated by a motley crew of buccaneers, rebels, and settlers. Survival require discipline and labor. These divisions reached a climax in mutinies and plots against the colonial leader, Laudonniere. La Roquette urged the settlers to seek out the rich gold and silver deposits rumored to be up the river. Why labor endlessly when wealth flowed in the rivers? (This is a question we must all ask, living in an over-developed, obese, and post-scarcity society.) Pirates used the colony as a base of operations against Spanish shipping. All in all “the malcontents too the opportunity to send home charges against Laudonniere of peculation, favoritism, and tyranny.” (66) A revolution was brewing before the colony had even got a real start. It was a libertarian experiment to be sure, but French weakness in the region and these internal divisions made it an easy victim of the Spanish.

Pedro Menendez de Aviles was the force that would bring the counter-Reformation to Fort Carolina. “The monk, the inquisitor, and the Jesuit were lords of Spain, — sovereigns of her sovereign, for they had formed the dark and narrow mind of that tyrannical recluse.” (83) This is the culture that created Menendez. According to Parkman Menendez used tyranny and military discipline to establish the Spanish colony of St. Augustine (just south of Ft. Caroline), sunk the French ships and marched on Fr. Caroline.

The details are not important, but the end result was the massacre of the French Huguenots for the dual crime of religious heresy (not being Catholics) and opposing the Spanish New World Empire. The chapter ends with the return of the favor, as Dominique de Gourgues sailed to the site of the former Ft. Caroline (the Spanish rebuild a fort there). Gourgues exacted his revenge on the resident Spaniards, but Menendez lived for another ten years.

Parkman believes this was a great tragedy for France’s new world empire. “It was [Menendez] who crushed French Protestantism in America. To plant religious freedom on this western soil was not the mission of France. It was for her to rear in northern forests the banner of absolutism and of Rome; while among the rocks of Massachusetts England and Calvin fronted her dogged opposition. Long before the ice-crusted pines of Plymouth had listened to the rugged psalmody of the Puritan, the solitudes of western New York and the stern wilderness of Lake Huron were trodden by the iron heel of the soldier and the sandalled foot for the Franciscan friar. France was the true pioneer of the Great West. They who bore the fleur-de-list were always in the van, patient, daring, indomitable.” (139)

Could France have sustained a place for the motley crew of religious dissenters, vagabonds, pirates, and runaway sailors? Maybe the defeat of this experiment in freedom was doomed. Maybe Parkman is aggrandizing its potential. The history of Ft. Caroline shows its internal contradictions, disorder, and tyranny. In any case, the Spanish did snuff out an interesting experiment that was not allowed to fully mature.