Despite his role in helping establish a democratic republic, George Washington’s time as commander of the Continental Army does reveal his continued commitment to a hierarchical society. I do not think there is any inauthenticity here. He does not seem to be interested in fighting for a democratic society. In his 1775 letter to Thomas Gage, he complained that “the Officers engaged in the Cause of Liberty, and their Country, who by Fortune of war, have fallen into your Hands have been thrown indiscriminately, into a common Gaol appropriated for Felons—That no Consideration has been had for those of the most respectable Rank.” (181) However, he is in some ways working toward a revolutionary army and was forced to come to terms with the democratic longings of the people he commanded. Perhaps some of Washington’s importance comes from his ability to make that transition from an aristocratic leader to one at least in dialog with a democratic people. In another letter to Thomas Gage, written just days, Washington begins to describe the difference between the American army and the British. “You affect, Sir, to despise all Rank not derived from the same Source with your own. I cannot conceive any more honourable, than that which flows from the uncorrupted Choice of a brave a free Poeple [sic] – The purest Source & original Fountain of all Power. Far from making it a Plea for Cruelty, an Mind of true Magnanimity, & enlarged Ideas would comprehend & respect it.” (183)

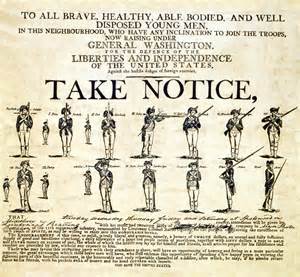

As any college freshman knows, Washington’s major achievement as commander of the Army was his sustaining of a regular, professional military at a time when the tendency for many American farmers was to join militias to defend their communities. I suspect that Washington’s difficulties were not just products of a frontier society lacking a traditional of military discipline. An emerging democratic society, engaged in a revolution was hostile to the very idea of a standing military. To his credit, Washington was aware of this and willing to work with it, even as he complained about discipline in many of his letters from the war period. “To bring Men well acquainted with the Duties of a Soldier, requires time – to bring them under proper discipline & Subordination, not only requires time, but is a Work of great difficulty; and in this Army, where there is so little distinction between the Officers and Soldiers, requires an uncommon degree of attention. . . . Three things prompt Men to a regular discharge of their Duty in time of Action, Nature bravery – hope of reward – and fear of punishment – The two first are common to the untutor’d, and the Disciplin’d Soldier; but the latter, most obviously distinguished the one from the other.” (210) Washington goes on to warn about the danger of too much freedom in the military. The high turn-over, mutiny late in the war, and lack of discipline seem to be the problems inherent in a revolutionary army that emerges from a democratic society. Even in his farewell address to the Army, he had issues of discipline firmly in his mind. At that point, he could look at it more optimistically praising the soldiers for overcoming local prejudices and replacing them with patriotism.

We do see the roots of Washington’s federalism in some of these documents. To John Parke Custis, he wrote: “It must be a settled plan, founded on System, order and economy that is to carry us triumphantly through the war. Supiness, and indifference to the distresses and cries of a sister State when danger is far of [sic], and a general but momentary resort to arms when it comes to our doors, are equally impolitic and dangerous, and proves the necessity of a controlling power in Congress to regular and direct all matters of general concern.” (418—419) During the demobilization of the Continental Army, Washington strongly supported a replacement with a “Militia of the Union,” which would have uniform discipline. In one of his last, wartime letters to his brother he again calls for a “Government of his Country” to avoid the evils of “Anarchy and Confusion,” which he thought would lead to tyranny.

Most of the letters and general orders and other documents collected in this section are tedious and of little interest to me personally. I admit to skimming through many of them. Most are concerned with provisioning the army and reports on military activities (mostly mundane). Some of the more interesting documents look at the attempts by Washington to find Indian allies, his quite liberal policy toward loyalists, preventing the activities of spies, his begging to state governments for funding, and his political concerns about currency policy. I shutter to think about the letters that the editor did not include. Ultimately, I am not finding George Washington to be all that interesting of a figure, but given his enormous task, he likely did not have much to perfect his writing or explore the deeper political and philosophical ramifications of the revolution he was integral in making successful. We leave that to Thomas Paine, who I wrote on early in the history of this blog. In the end, I think I am more interested in the common men and women who won the war. Looking through the commander’s eyes does not seem to take us very far. For Washington, these men seem to have been a problem to solve more often than they were heroes.