A common response to anarchist suggestions of the value of “intentional communities” (I think I am getting that term of Hakim Bey) is that they tend toward internal despotism, superstition or tradition. The historical evidence seems to support this fear. As scholars of American intentional communities have pointed out, they often were plagued by such problems. The Oneida, famously, had an odd cat running the show. John Humphrey Noyes implemented a form of group marriage called “complex marriage.” As described in the wikipedia entry for the Oneida: “Postmenopausal women were encouraged to introduce teenage males to sex, providing both with legitimate partners that rarely resulted in pregnancies. Furthermore, these women became religious role models for the young men. Likewise, older men often introduced young women to sex. Noyes often used his own judgment in determining the partnerships that would form, and would often encourage relationships between the non-devout and the devout in the community, in the hopes that the attitudes and behaviors of the devout would influence the non-devout.”

(Although, a place I would like to write about some day, Ceresco in Rippon Wisconsin, did not seem to have these problems and if anything was successful.)

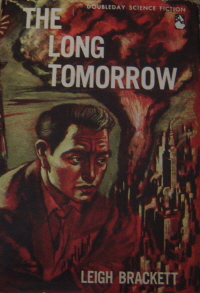

Another criticism of these intentional communities is that they seem to be doomed to failure if created in isolation, without the simultaneous destruction of the capitalist system. Again, the historical evidence for this is compelling. Few were able to exist for long without being affected by the outside world or facing corruption. Leigh Brackett in The Long Tomorrow addresses the second by placing her communitarianism in a post-apocalyptic world. The first problem, of superstition, authoritarianism, and ignorance, remains. Leigh Brackett was one of the few women active in the “golden age” of science fiction. She is most well-known for this novel and her work writing The Empire Strikes Back.

The Long Tomorrow is set after a nuclear war destroyed all the major cities of the world. The survivors – with an apparently functioning government and Constitution – banned many advanced technologies (but they are not complete Luddites), but their central law was the restriction of each community to 1,000 people or 200 buildings. This was to prevent the urban decadence that they survivors and their ancestors blamed for the war, as well as preventing nuclear way by abolishing any possible targets. These communities broke up into religious denominations such as the “New Mennonites” or “New Ishamaelites.” In their cloistered existence, a focus on community and hard work, an agrarian agenda, religious puritanism, and fear of the outside world, they certainly resemble the intentional communities in American history and even contemporary Amish or Mennonite communities.

The story follows Len Colter and his cousin Esau Colter, members of a New Mennonite community called Piper’s Run. Two events convince them to leave their home and search for the rumored bastion of technology and progress, Bartorstowm. The first event is their witnessing of the murder of someone suggested to be from Bartorstown. See, technology is considered so dangerous, religious zealots will even murder those who might threaten the stability created by the rejection of urbanization. In a later episode, the exiles reach a town where a local entrepreneur is killed largely for his effort to build a warehouse, which would have broken the 200 building limit. The second event is their discovery or a radio, which they try to understand using a “radiology” textbook. Awakened and curious, the cousins venture out to seek Bartorstown.

Eventually they make it there. Bartorstown is hidden in the Western mountains and is powered by nuclear energy and managed to a degree by a old supercomputer, both technologies are remnants from the pre-war period. The reader also learns that these are really “lifestyle technologists.” They are not interested in transforming the world or fully restoring a technological order. They are basically another intentional community, with no shortage of superstition, internal authoritarianism, and overall craziness. Len leaves Bartorstown due to these realizations and his difficulty in coming to terms with the technophobia he was born with.

One message in this tale is that small, isolated, “intentional communities” are prone to tyranny. In no case (and we witness three major communities in the novel) is change from within possible. Our heroes are only offered flight, exile, or death. There is no discussion of democratizing these communities. Whether technophobes or technophiles, tradition rules and the elders dominate. Len ran way or fled these communities three times. He ends convinced he cannot return home but the reader is uncertain there is any place for him.

Perhaps it exposes my sympathies for intentional communities that despite Beckett’s paranoia about the, I find her descriptions of them quite beautiful and moving. The critique of consumer society, technology, and in general the pre-war world are mostly convincing and remain relevant for our life. When Len’s grandmother reminisced about the consumer society of her youth, his father is quick to point out the shallowness of that culture. When the crisis came, consumer society collapsed people were doomed because consumerism reinforced dependency. “No, and I know because you told me how no food came in any more to the markets, and nothing would work on the farms because there was no power any more, and no fuel. And only those who had always lived without all the luxuries, and done for themselves with their own hands, and had no truck with the cities, came through without hurt and lead us all in the path of peace and plenty and humility before God. And you dare to scoff at the Mennonites! Chocolate rabbits! No wonder the world fell.” (395) The anarchist critique of technological systems (not technology working on a human scale) is not that dissimilar. How can we be free if we are dependent on systems of food and energy distribution? How can we be free when even minute of our lives depend on complex, and often unaccountable, bureaucratic systems?

I will have one more novel collected in American Science Fiction: Four Classic Novels, 1953–1956, but I can already sum-up a bit. The first three have questions that are interesting if approached from a libertarian perspective: resistance, consumer capitalism, intentional communities, cooperation, and the environment. None, however, provide easy answers. This might be striking considering the political culture of the U.S. in the 1950s, where easy answers, shaped by the ideological conflict between the Soviet Union and the United States, were used as a political bludgeon to crush dissent or alternative visions. I think it is a testimony to science fiction’s power to ask powerful questions that we find much greyness. (I will not likely review it in the blog, but Philip K. Dick’s Eye in the Sky is another great example of science fiction bucking the easy binary answers of the mainstream political culture.)

Next: Richard Matheson’s The Shrinking Man. See you tomorrow.

Pingback: Lynd Ward, “Gods’ Man” (1929) | Neither Kings nor Americans