Lynd Ward wrote graphic novels that did not require any words. He learned the technique from reading German attempts at constructing narratives from wood block prints. He introduced this method to the United States and created astoundingly expressive novels. This methods did not seem to evolve from the comics that might be the ancestors of contemporary graphic novels. Ward never read those early comic, having been forbidden by his strict, yet politically progressive, minister father. His six graphic novels were rooted in the tradition of 1930s populism. The “proletrianization of American culture” that historian Micheal Denning called the left-ward turn of 1930s culture is strongly expressed in these six novels. According to Denning, the strong Communist and socialist movements, the government investment in the arts, and the trauma of the Great Depression informed an entire generation of culture. (Indeed, we might add, it was the cultural milieu of the “greatest generation” if we want to participate in that generational hero-worship.) Gods’ Man is the first of Ward’s novels, published in the same week of the Stock Market crash of 1929.

Ward’s suspicion of the artistic merit of comics is laid out in a short essay he wrote on Gods’ Man (included in Library of America collection and completely unnecessary for understanding his tale). “It [pictorial narrative] has a long history and includes visual sequences in a variety of media. It ranges in time from the wall decorations in Egyptian tombs to contemporary comic stripes. The measuring stick, if anyone is making a list of what is or is not a pictorial narrative, is whether the communication of what is and what is happening is accomplished entirely or predominately in visual terms.” (779) Most comic books fail this test.

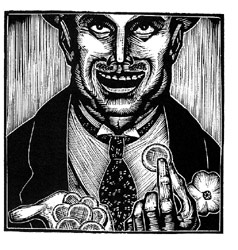

Gods’ Man is put together into five parts and contains 139 wood block images. Part one (“The Brush”) starts with an artist on a ship. He lands and observes a city in the distance. It is a modern city that reminds us of New York, with tall skyscrapers. He meets a beggar and gives him his last coin. When he arrives an a suburban village, he is taken in by an innkeeper but lacks the money to pay the innkeeper. He tries to pay with a painting but the innkeeper laughs. Apparently he is not such a good artist. A strange man pays his bill and looks at his work. He tells the artist that he owns a special brush, previously owned by the greatest artists in history. The artist can have it if he signs a Faustian contract. (The terms are not spelled out.) The artist signs it. He is like the proletariat. Not without skills, but hardly exceptional. Lacking any wealth but his mental and physical capacities. The Faustian bargain that all workers engage in is their willingness to sell their precious labor for mere survival.

Part two (“The Mistress”) explores the alienation from labor introduced by capitalism and helps explain why we so often accept that alienation. The artist enters the city and is overwhelmed by its power. He starts painting which the new brush. The people of the city are instantly amazed at his prowess and rich man offers to be his agent. The rich man immediately sells the painting he is working on to the eager public. He procures for the artist a penthouse studio, an apartment, and introduces him to the social elite, including “the mistress.” The artist is out of place among these people, but eventually finds his place among then, aided by alcohol. Bedding the beautiful woman incorporates him into that elite culture even more. The artist is there for the money he can make other people. Too naive to understand this now, he will come to learn that his alienation from his artistic work comes at too high a price.

Part three (“The Brand”) explores the broader alienation and atomization of modern urban life. “The mistress” admits she is only sleeping with the artist for money. He flees the apartment and wanders the city. Ward describes the loneliness and horror of urban life brilliantly in a few images of the artist wandering. He sees couples on the street, but always imagines the woman is “the mistress.” He imagines her laughing at his foolishness. This obsessions leads to an altercation with a policeman, who puts him in jail. He is able to escape by killing the man bringing his food. The artist is forced to flee the city.

Part four (“The Wife”) finds the artist escaping from the city to a pastoral paradise. Ward seems to dislike cities. This will not be the only time his characters flee the city for nature. A woman there nurses him back to health and shows him the beauty of nature by taking him to observe the night sky, far from the city. He falls in love with this woman and they have a child. He creates something of worth for himself, not for the rich man, and without the aid of the brush.

Part five (“The Portrait”) is set a few years later. The artist is training his son how to paint. The man who sold him the brush returns and asks for a portrait. The artist eagerly takes him up the mountain, thinking this will complete the contract he signed at the beginning. When the painting is near complete, the man exposes his face and revealed himself as a demon. The artist dies and the brush returns to its owner.

Gods’ Man explores several themes of importance to this blog. The first is the relationship between poverty/want and our alienation from our abilities. A second theme is the corruption of urban life and Ward’s clear preference for the countryside. Here I am more skeptical. Urban life provides a great number of alternatives for individual tastes and is inherently more flexible than rural communities. As I explored way back in the early days of this blog, intentional communities in rural areas can often be more internally oppressive than modern urban environments. Ward’s image of rural areas as single farmers or women in a cottage is simply silly.

If I were to interpret the entire story it is that the artist resemble the modern industrial working class. They sold themselves to capital for the possibility or success in urban environments. Even those who make it, like our artist, are being used and will be discard when no longer necessary for profit. The deal the proletariat made is Faustian. He cannot escape it horrors. The flight to the countryside is a mad fantasy. Ward will re-explore this theme in Wild Pilgrimage with a character who comes back from his time in the countryside with a desire to destroy capitalism. For Ward, this seems the more mature option. Both characters will die, but one will die as a victim and the other as a revolutionary.

Pingback: Lynd Ward, “Wild Pilgrimage” (1932) | Neither Kings nor Americans

Pingback: One Year Anniversary | Neither Kings nor Americans